Knowledge in the Age of Intellectual Atrophy

An illuminating prediction on the state of the world today

“We are drowning in information but starved for knowledge.” - John Naisbitt

Gilbert Highet’s book Man’s Unconquerable Mind is as illuminating as it is sobering. Published in 1954, late academic and intellectual critic Gilbert Highet predicted the possibility of a future that is already here. While not as well known as other thinkers of his time, Highet was well in tune to the current trends and potential consequences of living in the information age.

In the book, Highet examines the human mind, its limitations, and how humans come to seek out knowledge. He explores some of the potential consequences of living in the 20th century information age and unwittingly predicted a period where “bad” knowledge would eventually usurp “good” knowledge. He also identifies some trends that may keep people from becoming well-informed, independent, critical thinkers.

Highet demonstrates that the passive, mindless consumption of superficial information did not arrive with the advent of advanced digital technologies or the internet. It emerged well before this — with newspapers and magazines and radio programs. What we’re seeing today is merely an acceleration of what already existed.

Highet writes,

“…In the growing flood of useless and distracting appeals to our surface attention—rapidly written magazine articles, flimsy and fragmentary newspapers, and torrents of talk, talk, talk pouring from the radio—[libraries] provide a place to rest, be quiet, step off the moving platform of the Moment, and think.”

70 years ago, our waning attention spans were already a growing concern for scholars like Highet. And Highet believed that institutions like libraries would serve as places of refuge to escape from the incessant, distracting noise. While this solution may have been reasonable at the time, it’s no longer feasible for various reasons, chief among them being that we are drowning in information from all directions. The information war we’re waging won’t be won by a visit to the library. (It should also be noted that many libraries are underfunded ideological cesspools, which undermines the very ethos of learning).

Perhaps regrettably, Highet predicted the power of electronics and their ability to aid in learning and scholarship, though he could not have predicted how they would quickly come to replace learning altogether. Highet envisaged a calculating machine the size of a room capable of computing the equivalent of “several hundred mathematicians.” He also described a computation device he calls a “remembering machine” the size of a television set that could “scan, file, and on call repeat very word in a hundred-volume library.” We know how this story ends, but for Highet, these technologies were just emerging — at the time of the book’s publication, the general computer was just invented and primarily used by the military.

While Highet reserves some optimism for digital tools, he nonetheless insists that they do not compare to the inimitable brain.

Highet writes,

“The finest of all of these mechanisms is one which can store uncountable millions of facts throughout seventy years and which controls two cameras, two sound recorders, and ten agile and adaptable tools. It is the human brain.”

Tech utopians and Silicon Valley cheerleaders would disagree. It is not the human brain, but technology that would propel the information age forward.

Aware of the distractions that faced humanity, Highet expressed concern that the human mind would eventually commit suicide.

Highet writes,

“Suppose that the standard of living continues to rise all over the world, as it has done in the last century; that the population continues to increase; that its labors are shortened, its hours of leisure lengthened, its anxieties diminished, and its pleasures more lavishly supplied. Which will it prefer, learning or liquor? Art, music and books, or cards, dice, and horse races?”

He continues,

“All over the planet, as soon as men and women get a little money and leisure, something to lift them above the hunger of this week and the apprehensions of next year, at once their diversions tend to become either silly or disgusting . . . It is appalling to reflect upon the billions of hours and the masses of material which are utterly wasted every single day all over the world, by being thrown away on trashy amusements none of them providing more than a single day’s excitement, most of them offering much less, and all of them based on the idea of Having a Good Time, which really means having a momentary impulse and satisfying it.”

Based on the above, it’s reasonable to conclude that Highet anticipated that humanity would abandon the pursuit of scholarship and inevitably voluntarily offload mental processes from the brain to the latest technological device. As is made evident in these passages, Highet vacillates between optimism and tepid skepticism of the future of the information age. There seems to be an internal conflict that he’s grappling with as we progress further into the book.

I don’t doubt that if Highet were alive today he would be horrified at the state of the world and how far we have come in terms of our abandonment of intellectual stimulation and the pursuit of knowledge.

Researchers are already sounding the alarm on the impacts of AI on brain development, warning that regular use of AI accelerates cognitive atrophy and loss of brain plasticity, thus confirming the very real phenomenon of brain rot.

Highet also unwittingly predicted the rise of outrage culture and rage bait content. Although he did not define it exactly as such, he wonders whether humans might prefer “substitute bursts of emotional energy” in place of “sustained intellectual effort.”

Additionally, he expresses concern over our cognitive regression.

He writes,

“[People] may have become, like many primitive tribes, unable to read and write, incapable of organizing their experience into a logical pattern, impotent to plan for changes in the future or to recall the lessons of the past.”

We seem to be well on our way there.

U.S. literacy rates are in decline. Average reading scores for high school seniors fell to their lowest since 1992.

The English language is transforming at a faster rate than ever before, with many predicting a regression in the way we communicate. It’s also becoming more sterile, predictable, and homogenized with the advent of AI.

Despite what book lovers may say on #BookTok or elsewhere, book reading is also on the decline. A 2025 iScience study found that reading for pleasure fell about 40% over a period of 20 years, between 2003 and 2023. For those paying attention, this is unsurprising, but it is no less disconcerting.

None of this is aided by the fact that we prefer to consume short-form, fragmented, junk food content over quality, long-form content, which leads to a host of issues, as many of us are already aware.

Certainly it doesn’t help that platforms like Substack which once claimed to value long-form, thoughtful writing has opted for the growth-at-all-costs strategy, which means implementing features like Notes that make us angry, addicted, and alienated. People may complain about it, but they still find it impossible to resist, especially if the refusal to participate means compromising our visibility and, ultimately, livelihood for some. Some of the best Substack writers I follow have fallen into this trap. One recent example is Freddie deBoer who admitted to his struggle with Notes (which was obvious to those who noticed his recent outbursts starting ridiculous arguments with other writers).

In a recent post, deBoer wrote:

“When Substack rolled out Notes, it felt like someone had dropped Twitter directly into the middle of my professional life. Suddenly the thing I rely on to pay my bills came bundled with the very platform dynamic that has always been the worst for me: endless little arguments, personality contests, and the constant push-and-pull of online status. I hated the idea when it was being rolled out, not merely thanks to my own needs but also in principle . . .

Meanwhile, I’m sure there are many who just continue to write their newsletters and ignore the little notification button in the corner. In theory, I should be able to ignore it too. I mean, absolutely, as a functioning adult with free will, I should have the patience and self-control to just disengage from Notes. In practice, I can’t. My brain won’t let me. The result is that the newsletter profession, which already forces me to spend too much time as an internet personality, has become even more entangled with the kind of interaction and exposure that I know corrodes my mental health.

I’m not built for it, and it’s not built for me.

That’s been obvious for some time. What I need is a clean break, and that’s not going to happen while I’m still writing a daily newsletter.”

Suddenly deBoer’s petty online squabbles make a lot more sense. Still not excusable behaviour, but Freddie’s not the only one who is unable to resist throwing around ad hominem attacks and engaging in childish antics.

DeBoer says he’s unable to disengage from Notes because his “brain won’t let him,” but he’s not the only one.

Most of us are not built for these tools.

Yet most of us still participate, even if it causes us immense mental anguish. (And for those like Freddie who take out their internal struggle on other people online, it’s probably best to disengage altogether even if it may impact your income).

These digital distractions are just one of many that Highet calls an “incessant supply of petty pleasures.” For most of us, these petty pleasures are now portable, ones that we can carry with us 24/7.

Life is suffering, but it’s just a little bit more tolerable when you’ve got your little Pleasure Device always at your fingertips.

Highet notes that some critics believe that the pursuit of temporary pleasure is destroying the spirit and corrupting society. As an example, he brings up the introduction of opium in various countries as a way to pacify and distract the masses. Distraction via drugs and cheap entertainment is not new. Highet notes that Roman emperors hardly needed to police their citizens because they provided a steady supply of “free meals, frequent gifts of money, and in one year as many as 150 days of spectator sports—prize fighting (with swords, not boxing gloves), super-colossal three-dimensional pageants, and horse-and-chariot races.”

The steady supply of distractions aren’t much different today, we just have more options. Take your pick: Phones, TV, social media, gambling, junk food, drugs, alcohol, fleeting trends, fast fashion, and spectator sports are just a few of the vices that keep us pacified.

Most people, Highet notes, waste their intellect on the drudgeries of life:

“…[W]e must feel as sad as a doctor when he sees that the majority of of human bodies are badly fed, stupidly treated in their ailments, crippled by silly fashions in clothes and housing, sometimes allowed to degenerate through stupidity and sometimes maimed or deformed through malice.”

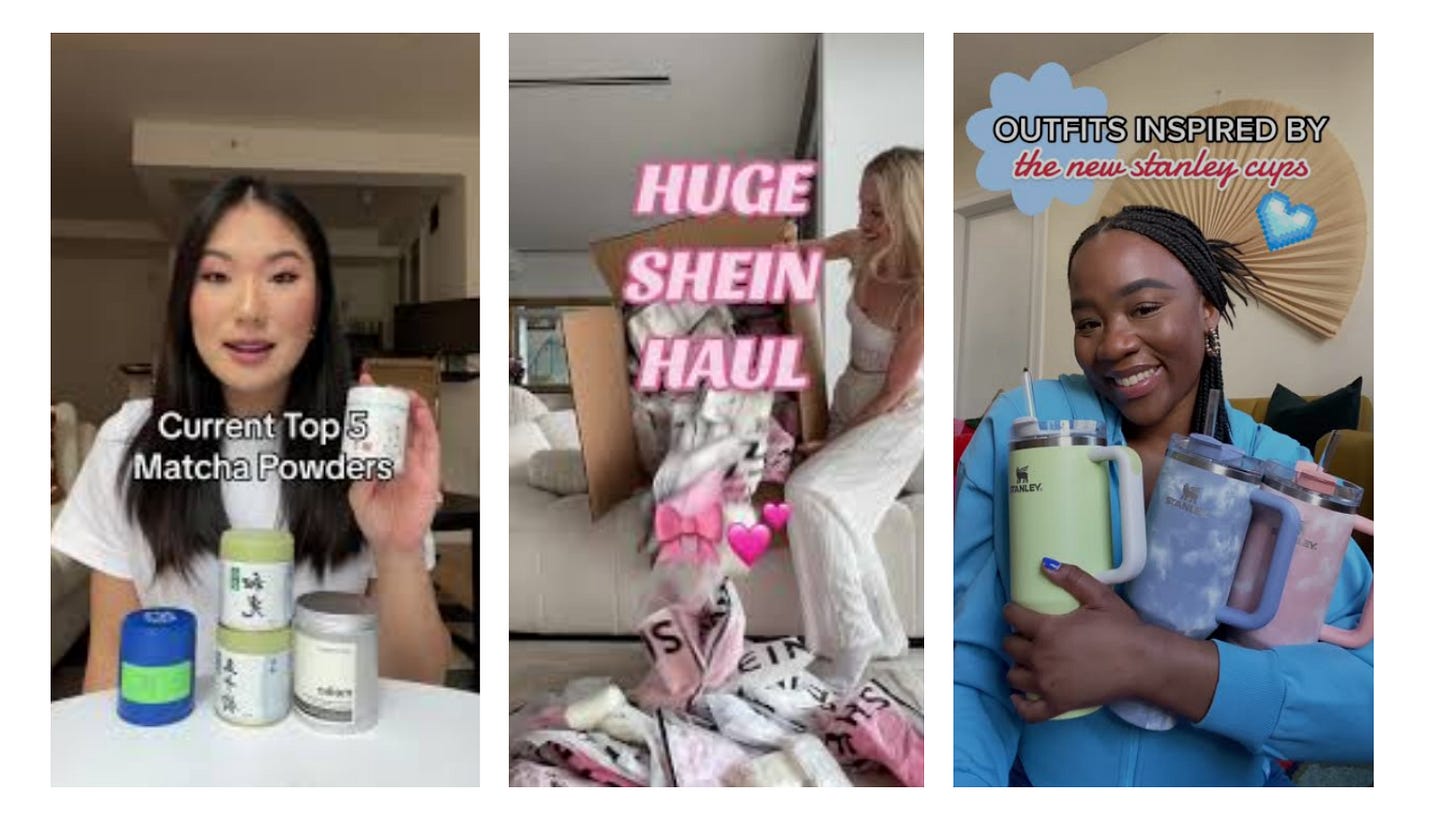

To compound the issue, consumerism is on the rise globally as more countries come out of poverty. Social media and other tools are creating even more good little hyper-consumers who have single-handedly created a microtrend culture which has led to more consumer waste than ever before. Every few weeks a new online consumer trend emerges and then fizzles out as if it never happened, only to be replaced with another. We’re currently seeing a global matcha shortage thanks to online influencers. Before that it was the obnoxious Labubu trend, and before that it was the Dubai chocolate bar, and before that it was the Stanley Cup. And then in between you have the Shein hauls, the Amazon hauls, the back-to-school hauls. And on and on it goes.

It’s easy to turn minds into mush and corrupt a nation when you provide a steady stream of entertainment, drugs, and anything else that distracts, stunts, and expunges the soul.

Knowledge, as Highet writes, may be “smothered unwittingly and witlessly by ourselves.” In other words, we are to blame for our own demise.

As many thinkers have pointed out, we are in the post-information age, but we’ve been here for several decades already.

Highet references this quote from T.S. Eliot’s The Rock (1934) which best summarizes his arguments:

“Here were decent godless people:

Their only monument the asphalt road

And a thousand lost golf balls.”

While there are more opportunities for deep learning to emerge, especially in alternative spaces, orthodox views and distractions still run rampant; low-quality junk content litters the information highway, and no matter how many of us speak out, we are still at the complete mercy of these tools.

It is clear little has changed since this book’s publication, and perhaps at this point nothing ever will.

“Most people respect knowledge, but they do not necessarily like it.” - Gilbert Highet

Fantastic piece. And much needed. I’ve been rereading Stolen Focus: Why You Can’t Pay Attention by Johann Hari, and it echoes your points (you’d love it).

If we can’t pay attention, we can’t organise.

Hi .. Very interesting article you have written. In case you have not come across yet, works of Jacques Elull dealing with very similar facets of modern technology and corresponding society - 1955 to 1995 period.